The presence of motorbikes was the first thing I noticed upon my arrival in Khandar, a tehsil in Rajasthan’s Sawai Madhopur district where I am currently working with Udyogini. They were all over. I didn’t see any mopeds or scooters. After two days, I saw a man driving an Activa. I pondered this observation and asked why, to which I was told, “Kyunki idhar aurat toh gaadi chalate hi nahi hain.”

This isn’t a question of who drives what type of vehicle. The emphasis is on the more important point of how uncommon it is to see a woman riding a two-wheeler in this region. Can we link the act to empowerment? Yes, I believe so. It is closely related to one’s ability to move.

Udyogini primarily focuses on women’s empowerment by empowering women entrepreneurs and assisting them in improving their livelihoods. A few years ago, the organisation collaborated with a woman who rode her two-wheeler to market the produce she grew on her farm. Even though it appears to be routine, it was a source of amusement for those who lived nearby. The men in the market are said to stare at her in disbelief, wondering what a woman is doing here. Wouldn’t it be better if this became a common occurrence in all areas? Shouldn’t it be considered normal for women to travel alone and engage in economic activities?

It is required because a woman’s identity must be distinguished from simply being someone’s wife or daughter to be recognised on her own. This will instil confidence in her and give her a sense of independence and individuality.

Let us now examine the region’s mobile phone usage. In the villages, only a few women own mobile phones. It is a fact that the girls are not given phones and are not permitted to purchase one before getting married. Then there’s a smartphone or an essential keypad phone. After marriage, the decision is determined by the affordability and mindset of the men in the house (the husband, brother-in-law, and father-in-law). When I asked why they didn’t have a phone, things got interesting.

They claimed that, because they lack adequate education, they cannot use smartphones and are not provided with one. However, this is not the case because most young girls and women know how to use it. They can also learn.

The men claim it’s all about “Maryada.” They believe that girls should not be given phones before marriage because “the system in villages is different from that in cities.” Other people may wonder if a girl speaks on the phone for long periods. They cannot be allowed to use the device casually because they will become spoiled. During their free time, they would use it for “wrong purposes” or “galat istemal.”

Many of the women I spoke with are aware of these viewpoints. They are, however, the ones who are outspoken and have some contact with the outside world. Like me, many others would take the time to reach out.

A woman can obtain a mobile phone before marriage if she begins working and, as a result, the phone becomes a necessity. One girl, for example, works as an E-Mitra, providing online delivery of various government services. Consider a situation in which a boy or a girl is sent (the word ‘sent’ is deliberate because she lacks the agency to make this choice) to study away from home, which is also uncommon in these villages. Only the boys are given phones in such cases.

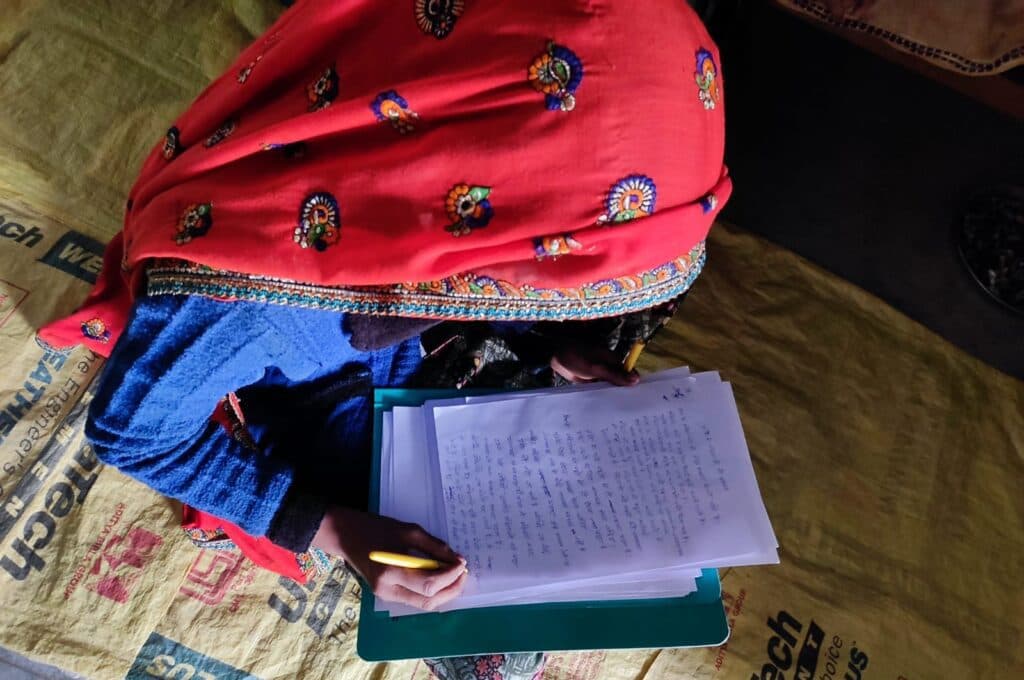

In one of our villages, I conducted a Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA), in which I asked women to list their concerns. Though I did not want to interfere with their listing, as a facilitator, I mentioned some of the challenges I had noticed and asked if they saw them as challenges as well.

The majority of houses do not have a bathroom or a toilet. Women had to take a bath outside and walk a short distance for their morning routine. They leave as early as 4 a.m., much earlier than men. Nonetheless, they never mentioned these as problems because they had accepted them as a part of their lives. “Bathroom toh chahiye lekin ab kya kare?” one asked. The bathroom in her house had been converted into a storeroom. Many women do not have the luxury of being able to take a dump whenever they want.

The majority of women and girls have never left Sawai Madhopur. Most men, like most women, have only travelled within a 100-150 kilometre radius and thus have little exposure to the outside world. This could be one of the causes of their lack of awareness and knowledge.

According to my understanding, the two most essential aspects of empowerment are choice and agency. Here at Udyogini, we have established a women-led and women-owned farmer producer company (FPC). They are the company’s shareholders and decision-makers. They must decide whether to distribute profits as dividends or to reinvest them in the business.

A male labourer had to be hired for a specific job. We made sure that the president and other female members of the company conducted his interview and decided to hire or reject him. In a few years, the goal will be to ensure that the FPC can function independently without the involvement of Udyogini.

Empowerment does not have to be these massive, all-encompassing breakthroughs or extraordinary achievements. It can be as simple as riding a two-wheeler, having the freedom to own a mobile phone, having a private space to take a bath, or having the ability to make one’s own decisions.

Author – Shreyas J (India Fellow)

बहुत शानदार आर्टिकल आपने शेयर किया है. पढ़कर बहुत अच्छा लगा.

Women empowerment

This was really informative.